THEME: FORGIVENESS

Here’s my longer sermon notes from this morning’s Metro Christian Centre service (dated 4th May 2025, aka, Star Wars Day), continuing our exploration of Jesus-shaped and Jesus-shaping habits.

You can also catch up with this via MCC’s YouTube channel (just give us time to get the video uploaded).

May the fourth be with you!

‘Ah, God! what trances of torments does that man endure who is consumed with one unachieved revengeful desire. He sleeps with clenched hands; and wakes with his own bloody nails in his palms.’—Herman Melville[i]

READ: LUKE 6:27-36 (NIV)

In Matthew’s gospel, in his Sermon on the Mount, Jesus puts it this way:

‘You’re familiar with the written law, ‘Love your friend,’ and its unwritten companion, ‘Hate your enemy.’ I’m challenging that. I say, love your enemies! Pray for those who persecute you! In that way, you will be acting as true children of your Father in heaven.’

Matthew 5:43 (MSG), 44-45a (NLT)][ii]

BOUND

Captain Ahab is not only bent on revenge but bent by revenge.

In the famous story, after losing his leg to the great whale, Moby Dick[iii], Captain Ahab turns that injury into an identity.

He’s so bound by his unrelenting hatred of this great whale, that he becomes as sinister, monstrous and destructive as the whale he is pursuing.[iv] Ahab is more of a threat to himself than the whale is, and it is his own obsessive hatred for the whale that ultimately paves the way to his own destruction.

This is sad in and of itself. But Ahab also manipulates his ship’s crew into a ‘devilish’ pact, binding them to his hatred and desire to enact vengeance. Which ultimately leads to their destruction, too.

In the final act of the book, during their blood-fuelled battle with Moby Dick, the crew are not only bound to each other and Ahab by this pact but also via the ropes from their harpoons, binding them to the deck of the ship. Ahab himself ends up entangled and physically bound to the great white bulk of Moby Dick by these same ropes. And with no means of escape, Moby Dick drags the whole lot downwards into a watery death.

But make no mistake, it’s Ahab’s hatred that is responsible for his crew being dragged into the hellish abyss of the sea.

He cannot forgive, and so he is consumed by hate. Ahab’s tragedy is not the loss of his leg—it’s the loss of his ability to let go, to release.

Of course, it’s a fictional tale. But Herman Melville’s epic novel tells an all-too-familiar story. Most of us have a “white whale” (or two) in our lives that has caused us grievous injury.

And though we may not go around seeking to physically harpoon those particular “white whales”—although sometimes we do—the temptation to get our own back, to get even, to have retribution and see that retribution as ‘justice’ is powerfully alluring. As such, our injuries often become our identities.

One novelist put it this way, ‘In hatred as in love, we grow like the thing we brood upon. What we loathe, we graft into our very soul.’[v]

LOOSE

I often wonder if this is what Jesus meant when he spoke about forgiveness and connected it with binding and loosing: ‘Whatever you bind on earth, you bind in heaven. Whatever you loose on earth, is loosed in heaven’[vi]

We can often read these words as if Jesus is granting us permission to do either; you’re free to bind or loose, it’s your choice. But what if Jesus is saying something more fundamental than this?

What if Jesus is explaining how the reactions to our injuries can either aid in releasing the world from all that entangles and ensnares it, or how our reactions can have the opposite effect of knotting it up even tighter? That there are reactions that release the life of God’s Kingdom into this world, and reactions that choke the expression of the Kingdom of Heaven.

According to Jesus, without the ability to let go, to forgive, hate has this way of binding us and our world, just like Ahab bound himself and his crew to the whale, into a destructive cycle.

I think Jesus is saying, ‘You have the power to do these things—to bind and loose, to forgive or to hate. I’m giving you great responsibility and great freedom. So, please make the most life-giving choice.’

I appreciate that the conversation of forgiveness is vast and that, for each one of us, it is complex. Forgiveness is not an easy, automatic thing for anyone. It’s not anybody’s default. It is a daunting task that seems impossible, a deeply personal process that can take time and that will be always uncomfortable. I have yet to meet a master of forgiveness.

To be clear, I’m not talking about the coffee being bad, or when traffic is busy, or the slow restaurant service, or the friend who forgets to text back. I’m not talking about the kind of stuff that exposes our lack of maturity, moments where we need to grow up. I’m talking about the real stuff.

People have done things to us that have left us broken and traumatised; things that have robbed us and depleted our experience of life. We carry injuries that have affected us and that still affect us daily.

So, I think it’s worth stating some things.

Forgiveness is not about excusing or explaining away wrong actions.

Forgiveness does not erase nor condone the harm done.

Forgiveness does not mean there will not be consequences.

Forgiveness does not mean that we make believe the injustice never happened, or that we make light of it.

And forgiveness does not mean we leave ourselves open to abuse. Forgiveness is not about permitting evil to be perpetuated.[vii]

But, with that last sentence in mind, forgiveness is how we avoid perpetuating evil.

On a personal level, it’s making sure this injury does not become my identity.

Corrie Ten Boom, who Helen also mentioned last week, certainly knew the effect of this. After the horrors of World War II, after her own dehumanising experiences of a concentration camp and after seeing her own sister, Betsie, perish in those camps, she set up a home in Holland for the victims of Nazi brutality. In this setting, she saw the impact unforgiveness and forgiveness had to bind and loose.

She writes, ‘those who were able to forgive their former enemies were able to return to the outside world and rebuild their lives, no matter what the physical scars. Those who nursed their bitterness remained invalids.’[viii]

In another place, Corrie Ten Boom writes, ‘Forgiveness is the key that unlocks the door of resentment and the handcuffs of hatred. It is a power that breaks the chains of bitterness and the shackles of selfishness.’[ix]

In her own life and the lives of her fellow victims, Ten Boom understood that without some level of forgiveness, her own identity would remain imprisoned and poisoned by the horrors of what had happened. She’s not alone in that experience.

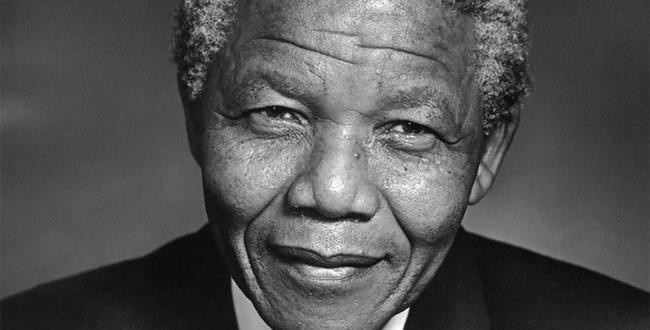

Nelson Mandela also understood this. He had experienced brutality under the Apartheid of South Africa—a brutality he had been non-violently resisting. But, as with the relationship with Moby Dick and Captain Ahab, that brutality began to generate its reflection. Hate began to generate hate.

In 1962 he was arrested and then imprisoned, in 1964, on charges of sabotage, spending 27 years under lock and key. Sleeping on damp concrete at night and, by day, toiling in a quarry under the glaring sun—work that permanently damaged his eyesight.

The former president of the USA, Bill Clinton, once asked Mandela how he felt on the day of his release in 1990, whether he hated all those who had imprisoned him. Mandela’s answer was pointed. ‘Absolutely’, he said. He had been abused, he had missed out on his children growing up, twenty-seven years with his wife and the best years of his life. He was seventy-two when he was released and had more than enough reasons to nurture resentment. ‘But’, Mandela added, ‘I realized that when I went through that gate, if I still hated them, they would still have me. I wanted to be free.’[x]

On a personal level, Mandela knew he would never be free without forgiveness.

But Mandela also knew this on a communal level—that without forgiveness, the hate and bitterness of the past would still have a binding grip on South Africa’s future.

As the historian, Tom Holland, describes it, it was during those long years of incarceration that Mandela began to grapple again with Jesus’ teaching about loving your enemies, and he came to recognise ‘that forgiveness might be the most constructive, the most effective, the most destructive tactic of all’ in a world entangled in the grip of retaliation and enmity.[xi]

On a communal and environmental level, forgiveness is the means of protecting ourselves from mimicking the behaviour of those who have wounded us, a means of resisting becoming a mirror image of the evil that has injured us.

On a communal and environmental level, forgiveness is refusing to allow our injuries to spill out and wreck more devastation upon our world. That, unlike Captain Ahab, we refuse to take the ship and crew with us. That instead of allowing the gravity of hate and resentment drag us with all and sundry towards an abyss, we intentionally steer another course.

What Nelson Mandela, raised as a Methodist, innately understood is that when choosing between revenge and forgiveness, it is only forgiveness that will lead to peace. That forgiveness is the only true act of sabotage.

Years before Nelson Mandela’s release, on another continent, a Baptist preacher called Martin Luther King Jr. had already been preaching this. He had been calling people who had been victimised, black Americans like himself, to recognise that hate doesn’t drive out hate, just like darkness cannot drive out darkness. Love, like light, is the only force capable of driving out the hate that darkens our world. Whereas hate multiplies hate; Violence multiplies violence.; Hard-heartedness multiplies hard-heartedness.

King knew that the ‘chain reaction of evil—hate begetting hate…—must be broken, or we shall [all] be plunged,’ like Ahab and his crew, ‘into a dark abyss of annihilation.’ And that the only way to break that cycle is to take seriously and follow Jesus’ admonition to ‘love our enemies.’ Only love can overcome hate.[xii]

That, breaking the laws of reciprocation, of our reactions matching the actions done to us, of tit-for-tat, we must intentionally ‘do good’. Regardless of the circumstances, we ‘do to others as we would like them to do for us.’[xiii]

To be clear, none of these people were content to leave the world as it is. The forgiveness of Corrie Ten Boom, Nelson Mandela and Martin Luther King Jr., was not a peace-treaty with the evils of the world. They sought for and worked for change. But they refused to echo those who injured them. They understood enemy love and forgiveness to be an aggressive act of pitting good against evil.

As the Apostle Paul said, ‘Do not be overcome by evil, but overcome evil with good.’[xiv]

Forgiveness is our refusal to bind ourselves and the world to the old-running order. Instead, we seek to create and release and embody a ‘haven of God’s new world in the midst of the old.’[xv]

FOOLISHNESS AND SCANDAL

Jesus said a lot about forgiveness, and he also made a “nasty” habit of it.

I say “nasty” only because, out of all the controversial things Jesus ever did, Jesus’ habit of forgiveness was at the top of the list.

To be fair, it still is.

The idea of forgiveness is something we wrestle with. Whether it’s the suggestion that we were in need of forgiveness, or our own personal struggle of accepting forgiveness, or how unjust it seems that God should even extend forgiveness to “them” (whoever “them” are), forgiveness always bristles, as the Cross of Jesus does, with either a sense of foolishness or of pure scandal.

I suppose that makes sense, though. Afterall, the cross is all about God’s forgiveness. The pierced body of Jesus is the embodiment of divine forgiveness toward us.

It would be fair to say that without forgiveness, Christianity as we know it would not exist. Forgiveness is at the very core of everything Jesus has done.

Whether it’s in his words to the paralysed man who was lowered on a mat before him[xvi]; or in his act of extending mercy to the woman caught in adultery[xvii]; or in his parable of a father who, joyfully and without hesitation, forgives his son who was lost, but now is found[xviii]; or even his own cry of ‘Father forgive them…’ in the midst of his own unmerciful execution[xix]—throughout the gospels, Jesus’ rhythm of releasing captives jumps of every page.

Jesus hadn’t come to bind people, but to set them free.[xx]

Again, it’s not that Jesus was condoning or applauding any of the evils of the world. Rather, he acts to overthrow the evil regime by doing good. I like the way Peter describes Jesus in Acts 10:38, ‘how God anointed Jesus of Nazareth with the Holy Spirit and power, and how he went around doing good and healing all who were under the power of the devil, because God was with him.’

More than this, Jesus called his own followers into this program of forgiveness and enemy love. As we’ve just read, in Luke 6, he’s very practical with his followers about doing good in return for harm. In Luke 11, as part of his prayer pattern, he teaches his disciples to pray ‘forgive us our sins as we forgive those who sin against us’. In Luke 17:4, he talks about forgiveness not being a one-time act, but a continual, recurring posture towards each other.

In Matthew 18, when Peter thinks he’s being super spiritual in suggesting an upper limit of forgiving someone seven times (three was considered impressive, but Peter doubles it and adds an extra one), Jesus ups the ante, suggesting it should be more like seventy-seven or seventy-times-seven times.[xxi]

It’s not meant to be taken as a literal number. Jesus is trying to get us to stop calculating and counting. Because, if you are keeping count, it’s not really forgiveness, it’s just postponing revenge.

Of course, within this conversation, Jesus does talk about speaking truth to those who harm and about the importance of those at fault repenting. But, he adds, ‘if they fail to repent, treat that person like a Gentile or a tax collector.’[xxii]

It’s an interesting instruction, since Jesus had a reputation for hanging out with Gentiles, tax collectors, and all kinds of sinners. He could not have meant, ‘shun that person’, ‘treat them like dirt’ or ‘be aggressive towards them’. Instead, he must mean treat them like everyone else who needs love and forgiveness.

It’s immediately after this that Jesus then explains to us that we have the power to bind or to loosen. Will we make the life-giving choice? Will we overcome evil with good?

Again, I know what you’re thinking, it’s just foolishness and scandal.

What Jesus teaches and practices sounds like the extreme.

And yet, he’s not the extreme, at all.

THE FALSE DICHOTOMY

Let me explain…

C. S. Lewis once said that the devil likes to send us errors in pairs; that the devil often gives us two wrong choices that are opposite to each other, two extremes, hoping that our loathing of one will gradually drive us toward the other.[xxiii]

In the case of forgiveness, those two extremes, that pair errors are often described as follows: Either we can act on our injury and seek revenge, or, at the opposite end, we should simply ‘forgive and forget.’

Neither of those responses are good.

As it’s Star Wars’ Day (May 4th), permit me to use the example of Anakin Skywalker, and the contrasting ideas of the Jedi and the Sith.

Anakin’s trained as a Jedi, soaking in Jedi ideology. But his life has not been one of peace and contemplative silence. He is a man with injuries: He experienced slavery as a child; he has witnessed the brutal and savage death of his own mother; and he fears the imminent death of the woman he loves.

Anakin knows trauma; the pain of it beats within his chest. But his Jedi teachers are telling him to deny his emotions, to forget all his attachments. It’s not wrong to love, to care, he’s told, but “love” at a distance. Don’t feel. Bury your feelings, because they’ll betray you. Deny the pain.

Rightly, Anakin, fundamentally understands this to be the wrong response, an inhumane response.

So, in his dislike of the Jedi’s approach, he gradually slips towards the opposite extreme of the Sith. The way of the Sith does not deny the pain, it does not instruct Anakin to simply ‘get over it’ or to ‘bury his feelings.’ However, the Sith teaching wrongly encourages Anakin to act on that anger, to be possessed by it and to seek revenge—which is equally inhumane.

Drawn by its embrace of his pain and in his loathing of one wrong extreme, Anakin is driven to the other wrong extreme, becoming the infamous Darth Vader.

In the conversation regarding forgiveness, often the bad advice, like that of the Jedi philosophy, has been to ‘forget’. But instead of resolving the wound, this merely pushes it down, covering it up, calling it something else. All it does is fester—your injury is still binding you to an inhumane identity. Understandably then, when forgiveness is understood as doing that, the temptation of embracing the other extreme of enmity is powerful because at least this other extreme has some level of empathy.

Occasionally, and wrongly, Christian teaching on forgiveness has been said and, sadly, modelled as a sort of forgetfulness. But Jesus’ teaching and practice of forgiveness is not about repressing or denying our injuries. Forgiveness is not the practice of emotional, physical or mental amnesia. Our injuries do hurt and the memories associated with them will recur.

We’re not called to be insensitive.

Additionally, wider than a personal level, I don’t think on a communal level that we could or should forget such things as the Holocaust, the Apartheid, the brutality of war, rape, child abuse etc.

A world that forgets its pain is not a better world.

A world that retaliates that pain is not a better world, either.

Forgetting the wounds, on one side, and seeking to wound, on the other side, are both wrong, inhumane extremes.

The way of Jesus is neither extreme. Jesus denies the validity of both of those reactions to suffering.

When God came to dwell among us, he didn’t become insensitive. God did not become impenetrable steel, he became flesh. He became vulnerable. The nail-pierced markings on the palms of his hands and the wounds on his body speak of the One who knows injury and insults, rejection and anguish, suffering and pain. Jesus, even in his resurrection never denies or plays down these wounds.

Jesus does not yield to the extreme of burying feelings or hiding the scars.

At the same time, even in the midst of his excruciating death, as Peter reminds us, he does not retaliate.[xxiv] He does not yield to the extreme of unleashing revenge or mimicking the evil he had suffered under.

Jesus’ way is not the extremes. Rather, Jesus holds his wounds and, in the light of them, determines to do good. He holds his wounds and the offer of peace together.

He calls us to follow this example.

We’re not called to banish those who persecute us from our minds, nor to persecute those who persecute us. Instead…

‘Pray for those who persecute you.’

‘Bless those who curse you.’

‘Do good to those who hurt you.’

These are not extreme responses. This way is the way that unbinds the world; the way that breaks the cycle; the way of peace.

DAILY BREAD

I have no idea what ‘white whales’ exist in your world. I have no idea of what wakes you up in the middle of the night. I have no idea what triggers painful memories for you, or how paralysing that can be.

What I do know is this: No one gets through life unscathed. It is impossible to imagine that anyone could live without experiencing some hurt and offense. Furthermore, who can honestly say that they have never hurt another? We’ve all got white whales, and we are most definitely someone else’s white whale.

What I do know is that forgiveness is the only valid solution, and I do not mean some one-time event that then we move on from. It’s like weeding a garden. It’s like the daily, ongoing task of laundry—the basket empties and then refills needing to be emptied again. It is a work that is, in some ways, never done. For each of us, it is a daily rhythm to be intentionally practiced. In our own lives, we face daily choices to forgive or hold grudges; to bind or to loose; to do evil or to do good.

I’m not asking you to ‘get over it’ this morning. I’m only asking that you and I will refuse to be bound to or bound like those who have injured us. And that we will seek to be like the one who has liberated us, and to loose others as he has done.

I was going to include an amazing story, in which Corrie Ten Boom, years after her release, encounters one of the ex-guards at the concentration that imprisoned her—a guard that asks for her forgiveness.

It’s a powerful and inspiring story, but I’ve chosen not to mention it, only because stories and sermons cannot teach us the how of forgiveness no matter how well intentioned they are.

Forgiveness is something we only learn from experience, in that ongoing task of bringing our wounded selves to our wounded and risen saviour again and again; asking daily for help in holding these wounds the right way; asking Him how we carry these wounds forward; asking Him how these wounds can be avenues of healing in our world.

It may be that, for you, in that approach, it happens instantly, and you feel this overwhelming release and sensation of God’s love aiding you in miraculously loving others. If it does, amazing!

But it is no less amazing to exercise a day-by-day persistence in asking God to help us do what we often cannot imagine ourselves doing or even wanting to do.

When Jesus taught us to pray, it’s no small coincidence that our prayers for forgiveness are immediately preceded by our need for daily bread, the life of God. Without the Spirit of God, this sort of act is humanly impossible. But with God, and in the timing of God, everything is possible.[xxv]

Lord God, we recognise the wounds we bear.

Help us to carry them as you carry yours.

Amen.

‘Put away every kind of bitterness, anger, wrath, quarrelling, and evil, slanderous talk. Instead, be kind to one another, compassionate, forgiving one another, just as God in Christ also forgave you.’

—Ephesians 4:31-32 (NET)

ENDNOTES AND REFERENCES

[i] The narration of Ishmael, contemplating the infamous Captain Ahab in Herman Melville’s classic Moby-Dick (Penguin Popular Classics, Penguin Books Ltd, UK, 1994), Ch. 44, p. 201

[ii] Although the instruction to ‘love our neighbour’ is from Leviticus 19:18, it’s important to state that the law, the Torah, nowhere states ‘hate your enemies.’ Jesus and his audience would be aware of this, even though we can be selectively unmindful of it. Jesus’ teaching here is not a push against anything that Moses explicitly states, but rather a push against a particular understanding and reading of the Torah. In most translations, the quotation marks (not present in any original manuscript, as quotation marks, like other literary grammatical features, such as question marks and commas, etc., are a “modern” invention) finish intentionally after the ‘love your enemies’ statement, if included at all. This is done to highlight that Jesus is not speaking directly against the Torah but against a human teaching of the Torah that implied hating one’s enemy was a mutual accompaniment to loving one’s neighbour. This is made clearer with Jesus’ wording, ‘You have heard it said…’ For this reason, I prefer the way Eugene Peterson rephrases the beginning of the sentence, where he contrasts what is ‘written’ to what has been interpretatively added (‘unwritten’) by certain conventional understandings.

As a topical aside to what will follow, this isn’t the only time Jesus uses this verse in Leviticus (Love your neighbour) to speak of one’s understandings of what is written in the Law. In Luke 10:26, Jesus, responding to a question about eternal life, asks a Torah expert not only what the Hebrew text says but also how he understands it: ‘What does the law of Moses say? How do you read it?’ (NLT, emphasis added).

As Amy-Jill Levine points out, ‘Leviticus does not explicitly require [the Torah expert] to love his “enemy” … In Jewish thought, one could not mistreat the enemy, but love was not mandated. Proverbs 25.21 insists, “If your enemies are hungry, give them bread to eat; and if they are thirsty, give them water to drink” (Paul cites Prov. 25.21-25 in Rom. 12.20). Only Jesus insists on loving the enemy: “Love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you”. He may be the only person in antiquity to have given this instruction.’

However, Levine goes on to add that how one read Leviticus could lead to enemy love. ‘In Hebrew the words “neighbour” and “evil” share the same consonants (resh ayin); they differ only in the vowels—but ancient Hebrew texts do not have vowels. Both words are written identically. And so, ‘When Jesus asks the lawyer, “How do you read?” he is therefore asking, “…are you able to see, in the very words of the Torah, the equation of enemy with neighbour and thus the command to love both?” The lawyer has read the words in Hebrew, but he cannot see their full meaning.’ [Amy-Jill Levine, Short Stories by Jesus (HarperOne, An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers, 2015), pp. 93-94]

[iii] Or should this be Moby-Dick? The debate continues…

[iv] If you ever take the time to read the book, and I would encourage you to do so, you’ll notice that sightings of Ahab in the narrative are as rare as the sightings of the great whale. Like Moby Dick, news is often reported about Ahab’s whereabouts in hearsay almost as proportionally mythical as Moby Dick’s legend, and there’s generally an ominous tone whenever he does emerge above the waves of these rumours.

[v] Mary Renault, The Mask of Apollo (Virago Modern Classics, Little, Brown Book Group, London, 2015, Kindle Edition), Loc. 994. For some reason, this quote is often wrongly attributed to the psychologist Mary Ainsworth and her co-authored work Patterns of Attachment: A Psychological Study of the Strange Situation

[vi] Matthew 16:19; 18:18; John 20:23

[vii] Although it’s not the focus of this particular sermon, I do feel it’s important to state that Jesus does not call us to place ourselves in positions of abuse.

While it is true that, at times, persecution may be inevitable and inescapable, this does not mean that we should not seek to protect ourselves from persecution at other times. In Acts 8:1, a wave of persecution hits the church in Jerusalem and the believers flee into Judea and Samaria. There is no tone of condemnation in this report. In Acts 9:22-25, Paul escapes Damascus in a basket to avoid a plot against his life. In Acts 9:29-30, Paul leaves Jerusalem to avoid another plot to murder him. In both cases, other believers facilitate his removal from harm. In Acts 14:5-6, both Paul and Barnabas are warned (one presumes through other believers) of a plot to have them stoned—they leave Iconium as a result. Similarly, in Acts 22:17-23, Paul shares his testimony of being encouraged by the Lord to flee the persecution he would face in Jerusalem and to go to the Gentiles instead. In response to this testimony, Paul, again, finds himself facing a dangerous mob. A Roman commander pulls Paul from the mob and orders him to be lashed for instigating a riot, but Paul has no qualms with using his Roman citizenship to avoid this harm. In Acts 23, Paul calls on the Torah and his heritage as a pharisee to, once again, appeal against persecution.

Again, there may be times when persecution is inescapable, but we are nowhere encouraged to give ourselves to it undiscernibly.

In a similar way, in the context of domestic abuse, I would not suggest that Jesus instructs a continued exposure to abuse, and I would encourage people to remove themselves from such situations. Additionally, like the actions of the believers in Acts, that we would also seek to remove others from contexts of harm where possible.

Someone may wish to argue that Jesus gave his body to sufferings, and that we should follow his example. While true, it should not be forgotten that there is something unique in Jesus’ own redemptive sufferings and sacrifice, and that Jesus only gave up his life when he knew the time had come. People had already attempted to kill Jesus in a previous episode of his ministry, and he slipped away through the crowds and left them (Luke 4:29-30). This should not be overlooked.

There may even be times when, like the non-violent resistance of the American Civil Rights movement, we allow ourselves to suffer in order to expose inhumanity. But again, this is a unique situation prompted by a unique pressure and by no means a universal posture. Jesus’ teaching on turning the other cheek should be understood in this context of oppression. There may be even times when we lay ourselves down for others, too, coming between them and harm. But this again, is a unique situation, quite different from one where domestic abuse is perpetuated.

To repeat what I said in this sermon and to state what I will go on to say: Forgiveness does not mean leaving ourselves or others open to abuse or having to remain in an abusive context if there is a way out. Rather, forgiveness means overcoming evil with good and not retaliating in kind.

[viii] Corrie Ten Boom, excerpted from I’m Still Learning to Forgive from Guideposts Magazine (Guideposts Associates, Carmel, NY, 1972).

[ix] Corrie Ten Boom, Clippings from my Notebook

[x] Excerpted from Bill Clinton’s Introduction to Nelson Mandela, Long Walk To Freedom: The Autobiography of Nelson Mandela (Abacus Books, An imprint of Little, Brown Book Group, London, UK, 2013), p. 2. Kindle Edition.

The quote often attributed to Mandela goes like this, ‘As I walked out the door toward the gate that would lead to my freedom, I knew if I didn’t leave my bitterness and hatred behind, I’d still be in prison.’ While these words certainly capture Mandela’s sentiment, I’m not convinced they are a direct quote. Well, I haven’t been able to source them directly yet. They are certainly not from Mandela’s autobiography. If you know the source, please let me know.

[xi] Tom Holland, Dominion: The Making of the Western World (Abacus Books, An imprint of Little, Brown Book Group, London, UK, 2020), p. 487

[xii] Martin Luther King Jr., A Gift of Love: Sermons from Strength to Love and Other Preachings, Loving Your Enemies (Penguin Books, Penguin Modern Classics, 2017), p. 49

[xiii] William Barclay notes that Jesus’ words are unique in the ancient world. Other moral and ethical teachers/philosophers of the ancient world, such as Philo, Isocrates and Confucious, only supply a negative form of this teaching. I.e., ‘What you do not want done to yourself, do not do to others.’ Whereas Jesus teaching is positive; it does not consist in not doing things but in doing them. [William Barclay, The Gospel of Luke: The New Daily Study Bible (Saint Andrew Press, Edinburgh, 2010), pp. 94-95].

John Nolland comments that Jesus’ teaching of enemy love is ‘not as uniquely Christian as is sometimes maintained’, giving examples from early Babylonian sources, Seneca and Epictetus, among others. However, Nolland also notes that these other sources are, without exception, always concerned with moral consistency or with an ethic of reciprocity; ‘one acts in a generous way in order to make friends so that in future one may get return from these friends.’ In contrast, Luke saw Jesus’ teaching as radically critical of such a self-serving ethic. Jesus’ ethic denies any reciprocity, and is a breaking of the chain of action and reaction, compelled by an imitation of God that ‘stands in sharpest contrast to the most common view of enmity in the ancient world: “I considered it established that one should do harm to one’s enemies and be of service to one’s friends” (Lysias, Pro Milite 20).’ [John Nolland, World Biblical Commentary, 35A, Luke 1-9:20 (Thomas Nelson Publishers, Nashville, 1989), pp. 294-299]

Theologians Amy-Jill Levine and Ben Witherington III, importantly note that the Old Testament provides a backdrop to Jesus’ instruction of ‘doing good to those who hate you.’ Proverbs 25:21, as noted above in endnote ii, already mandates giving bread and water to our hungry and thirsty enemies. As noted above, this was more of a prohibition against mistreating one’s enemy more than a command to love them. As Levine and Witherington are quick to add, Jesus’ ‘requirement to love enemies is an intensification’ of this earlier Jewish material. Additionally, they note that the apocryphal work Tobit has a similar injunction, ‘Do not do to anyone what you hate.’ As Barclay noted above, however, Tobit’s injunction is also formed in a negative proposition, quiet unlike Jesus’ positive injunction ‘to do’. [The Gospel of Luke: New Cambridge Bible Commentary (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge UK, New York USA, 2018), p. 180, emphasis mine]

[xiv] Romans 12:21

[xv] Miroslav Volf, Exclusion and Embrace: A Theological Exploration of Identity, Otherness, and Reconciliation (Abingdon Press, Nashville, US, 1996), p. 116

[xvi] Luke 5:17-26

[xvii] John 8:1-11

[xviii] Luke 15:11-32

[xix] Luke 23:34

[xx] Luke 4:18-19

[xxi] Matthew 18:22

[xxii] Matthew 18:17

[xxiii] C. S. Lewis, Mere Christianity (HarperCollinsPublishers, London, UK, 2001), p. 186

[xxiv] 1 Peter 2:21-23

[xxv] Due to the scope of what I wished to cover this week, I didn’t have time to talk about the rhythm of confession which is inextricably tethered to the matter of forgiveness. As a brief summation, taken from my rough outlines of this series:

With confession we abandon self-justification for the things we have done, acknowledging the pain and hurt we have caused. It’s common these days for people to take a ‘personality test’ and use as it as an excuse for behaving the same. But God is working to shape each of us of us into Christlikeness, regardless of our personality type or ‘enneagram’.

Confession can only happen where trust and humility exist. With a few close friends in Christ, we can remove our masks, become transparent, laying down the burden of pretence. Allowing ourselves to be engaged with at the deepest level for the sake of transformation.

More than this, confession helps us experience and know the forgiveness of others and God. Although we pray for forgiveness, we do not feel it ourselves until we have confessed it to another person and see/know that forgiveness embodied and modelled toward us. For this reason, God has provided other Christians to ‘make God’s presence and forgiveness real to us.’ (Richard Foster, Celebration of Discipline, p. 129).

As Dietrich Bonhoeffer claims, ‘he who is alone with his sin is utterly alone’ and ‘the more isolated a person is, the more destructive will be the power of sin over him.’ (Life Together, p. 86-87).

God does not want this isolation for any of us.

Confession builds our faith, and nourishes the depths of our souls, as God provides for our needs through his people.

Leave a comment