THEME: Identity, Loyalty and the Kingdom Tension

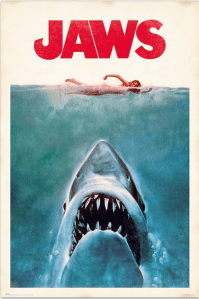

Here’s my longer notes from this morning’s @mccbury service, beginning our FREE TO GOD series exploring Paul’s letter to the Galatians. This first session, I hope, will help us get to grips with the Jaws-like threat Paul is dealing with.

Please note, I felt led to say some additional things this morning, not included within these notes, relating to our current times and the temptation to give our allegiances to other ‘no gospels’ that mute the announcement of God’s Kingdom. You’ll have to visit Metro’s YouTube channel to hear this context.

You can also catch up with this via MCC’s YouTube channel (just give us time to get the video uploaded).

‘Not fare well,

But fare forward, voyagers’

—T. S. Elliot[i]

READ: GALATIANS 1:1-10 (NLT)

A BIGGER BOAT

As a huge movie fan, I love it when anyone drops a movie quote into a conversation.

The problem is, the older I get, the harder it is to remember the films the quotes come from.

Having said this, the other week someone dropped the following iconic movie quote into a conversation, and I knew the film it was from instantly:

‘You’re going to need a bigger boat.’

You may recognise it?

For those who (shamefully) don’t, it’s from the 1975 Spielberg classic, Jaws (If you’re keeping count, that was half a century ago!)

Jaws (1975)

This iconic line is delivered when Chief Brody (played by Roy Schieder) catches his first terrifying glimpse of the monstrous shark, backing away from the edge of the boat towards the so-called “safety” of the boat’s cabin. The words are half-mumbled in a tone of dread and disbelief, a moment of sudden perspective, as Chief Brody realises they have underestimated the size of the shark they are hunting; the threat they’re facing is far more dangerous—and far larger—than they had initially anticipated.

Galatians is little like Jaws.

With where we are in history, we often come to Galatians with the glasses given to us by the great debates of the sixteenth century, with Reformation-era lenses, as if the only thing Paul wants to talk about is whether we are justified by faith or by works.

And while that’s not unimportant—it is certainly part of what Paul has to say overall in Galatians and it was, in fact, life-changing for someone like Martin Luther to ‘rediscover’; And while, I’m sure, Paul would have applauded Martin Luther’s defence that we are justified by faith and not by the works of the law—to read Galatians only through that lens is to miss the context of Paul’s world and the real-world struggles of his audience.[ii]

To be blunt: we’ve shrunk Galatians and, to borrow that iconic line from the movie Jaws, ‘You’re going to need a bigger boat.’

Like Chief Brody in Jaws, we often underestimate the size and seriousness of the threat Paul is dealing with. This isn’t just about tweaking someone’s theology. Paul sees something massive and dangerous on the horizon—something that threatens to devour the very heart of the gospel and fracture the unity of God’s people.

If we’re going to understand what Galatians is about, we need a bigger boat—a bigger theological imagination, a bigger historical lens, and a much bigger view of what God is doing through Jesus the Messiah.

Galatians is not just a treaty on works and faith—it’s a manifesto about God’s new creation, about belonging in the family of Abraham, and about living in the tension between two worlds.

It’s about identity—not just who we are privately, but what kind of people we are publicly. It’s about how we live in the world now that God’s kingdom has broken in—a world where the old empire hasn’t yet gone away and still looms large.

WE AIN’T IN KANSAS…

Paul is not a happy bunny.

In the first few verses of Galatians, Paul does something he rarely does: he skips all the formal pleasantries.

Most of his letters open with a prayer of thanksgiving.

But not here.

There’s no warm greeting, no gentle lead-in, no encouragement or praise of his audience. Paul is urgent. Disturbed. Even angry. One writer rightly describes Galatians as Paul’s most passionate letter—you can almost feel his outrage leaping of the page:[iii]

‘I am astonished’, he writes, ‘that you are so quickly deserting the one who called you to live in the grace of Christ and are turning to a different gospel—which is really no gospel at all.’ (Gal. 1:6-7a, NIV)

Paul isn’t writing as a professor debating abstract doctrine. He’s writing as a father watching his spiritual children walk toward danger. For him, the gospel isn’t just good advice or correct belief—it’s ‘good news’, it’s the announcement of a new reality.[iv]

It is the declaration that in Jesus the Messiah, God’s promised future has already begun, that God’s promised new age has broken in, that, because of Jesus’ cross and being raised from the dead, the old age has been overturned, the world has changed, and that our very identities have been redefined as a result.

Paul shared the common Jewish understanding that human history could be divided into two ages:

The present age—marked by sin, death, idolatry, injustice, the horrors of humanity’s inhumanity.

The age to come—the time of God’s kingdom, when sins would be forgiven, death defeated, the Spirit poured out, and creation renewed.

The common understanding was that when God’s rescue came, that present age would cease immediately, and then the age to come would begin. Think of it like one line stopping and another line commencing.

Where Paul departed from his contemporaries was in his conviction that the age to come had actually already begun—it had been inaugurated, installed if you prefer, with the death and resurrection of Jesus and with the gift of the Spirit. The present age hadn’t ended, though. Rather, the new world had begun within the midst of the old.

Paul, as he writes elsewhere, and as other New Testament writers explain, understood that one day this ‘present age’ would end, that, one day death would be no more, creation would be renewed and, for those who have died, resurrection; and for those alive at the time, also a resurrection—a taking off of that which is prone to decay and corruption and a putting on of that which is immortal and incorruptible.[v]

But Paul is clear, the decisive battle had been fought, and the victory had been won through the cross and resurrection of Jesus—the rescue has happened! New Creation, God’s Kingdom, wasn’t something we were waiting for—even though we await its consummation—it’s something the Holy Spirit has already brought to us.

In one of his other letters, Paul puts it this way, ‘If anyone is in Christ Jesus, New Creation!’[vi] In other words, we are now, here today, participants and citizens of God’s Kingdom, God’s new world.

Creation may still await it’s release from all that ensnares it, but humanity’s shackles had been smashed.

As Paul says in the opening of this letter, through Christ, believers have been rescued from the power of this present evil age (v. 4). When Paul says ‘rescued’, or ‘delivered’ as some translations word it, he is deliberately using the language of the Exodus story.

And make no mistake—Paul sees the cross as the New Exodus. Jesus did not come primarily to model morality or provoke philosophical reflection. He came to save. The cross is not solely a display of Divine love—it is also a cosmic victory. Just as God once delivered his people from Pharaoh’s grip, now through Jesus, God has defeated a far greater set of enemies: not just sin, but all that oppresses human life—injustice, violence, death, and the demonic forces behind them.

Jesus’ death confronts and conquers every enslaving force that holds humanity in bondage! The power of that old world has been defeated and our enslavement to it has been broken. We are no longer slaves under the tyranny and authority of sin, death, and Satan. For freedom Christ has set us free![vii]

But, at the same time, the old powers haven’t yet let go of the world around us. We have been delivered from their power, but not their presence. They are defeated, but they still exert their influence. Greed, War, Dominance, Brutality, Injustice, Envy, Apathy, Dehumanisation … people still, sometimes blindly, sometimes knowingly, give their allegiance to these defeated powers, choosing to prop up the old order.

And so this is the tension: we belong to the future, but we live in the present. The Kingdom of God has dawned, but the sun hasn’t yet died out on the old. We must still live in a world that is under the influence of the old age—and feel that tension as we await the day when God will put a full end to everything associated with the present evil age.

As Paul would describe it in his letter to the Philippians. ‘We are citizens of Heaven, a colony of Heaven where Jesus reigns! … And we are also eagerly waiting for him to return …’[viii]

We live in the overlap of the ages—what theologians would call the “already but not yet” of God’s Kingdom.

But make no mistake, the world is different, the coordinates have shifted—God has acted, God is with us, Jesus Christ is Lord.

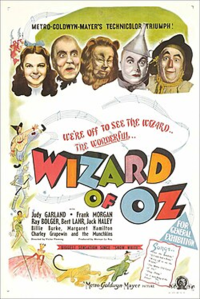

If Paul were writing today, and he wanted to use an iconic movie line to help us grasp this, then maybe he would echo Dorothy from The Wizard of Oz, ‘We ain’t in Kansas anymore.’

Wizard of Oz (1939)

The world, as Paul’s original audience knew it, had changed. And Paul is writing to help them—and us—understand how to live in this in-between space.

A FAILURE TO COMMUNICATE

Again, for Paul, the gospel is not merely a formula for salvation—it is the announcement of a new creation, a new Kingdom, a new Lordship. And that new creation gives birth to a new family.

For centuries, the Jewish people—Paul being one of them—had been carriers of this promise that God would act to renew the world, bringing about the new age. They had lived, I suppose, as living signposts that this would happen. And like all good signposts, they were distinctive— the ethnicity of this people was defined by the boundaries of the Mosaic Law. Torah observance to circumcision, Sabbath laws, food laws etc., marked them out as ‘The people of God’, the people who carried and communicated this promise of God’s.

This promise, as Paul will mention later in this letter, originally came to Abraham. God had promised Abraham that through his offspring, God would bless all the world and make Abraham a father of many nations. In other words, because of Abraham’s offspring, all the peoples of the world would become ‘The people of the One true God.’

As Paul will go onto explain in this letter, Jesus is that offspring, born under the Torah, representative of this people, who, through His faithfulness, brings about the fulfilment of the promise. And because a new creation has come, a new, expanded family has also been formed—Abraham’s children are no longer solely Jewish, but also non-Jewish; Gentiles (to use a word we meet again and again in the New Testament).

This family is now made up of both, together.

In a nutshell, this means that:

Being Christian does not mean becoming Jewish. Paul is not anti-Jewish; we need to be clear on that. There is no room for antisemitism in Galatians. But he is clear: the covenant has expanded; the age of the law has reached its goal; the New Creation has begun; and the people who belong to that world are those who are “in the Messiah”—regardless of their ethnic origin. This family is not defined by ethnic boundaries or Torah observance anymore, it cuts right across the ideas of Roman identity, Greek biology, Jewish ancestry. It is defined by faith in the Messiah and evidenced by the gift of the Holy Spirit.

But, at the same time, being Christian does not mean becoming culturally homogenous, culturally blank. You don’t have to erase your ethnicity. We can often overlook the fact that Paul, even while following Jesus, still identified as a Jew (see Gal. 2:15, for example). Paul never abandoned his Jewish identity, and neither did he call other Jewish Christians to do so, either. At the same time, Paul never called Gentiles to become Jewish. We retain our ethnicity—they are beautiful things to be celebrated.[ix]

As Paul will explain in another letter to the Ephesians, it’s the coming together of all this ethnic diversity that shows and proves the wisdom of God and the greatness of His rule to the nations.[x]

And so, to live in Christ is not to become Jewish, nor is it to erase our cultural heritage. Paul will later write that in Christ there is neither Jew nor Gentile, but that’s not because ethnicity is meaningless—it’s because in the Kingdom, no ethnicity is superior. In God’s family, we are one—there are no grand kids or second-class citizens, not because we are the same, but because we are united in Christ.

As Paul will explain near the end of this letter, whether we are circumcised or not circumcised makes no difference. What matters is loyalty to this One true God, or faith[xi] as he calls it, expressing itself in love[xii]; what counts is New Creation, as he’ll say at the very end.[xiii]

It’s not our biology or ethnicity that has qualified us to this new identity and brought about belonging to this new era, this new family. As Paul boldly makes clear in his opening statements (v.4), this has all come about because this project has been God’s intention and God’s action.

To God alone goes all the glory. To put that in modern terms, the credit is all His, now and forever—we cannot boast in our genealogy or ability to follow laws. This identity is a gift. You don’t earn it. You don’t inherit it biologically. You receive it through grace—through God’s own act of inclusion. This is God’s plan, and it’s always been God’s plan.

Paul has understood this for a while—he hasn’t always understood this, as we’ll see next week. But for some time prior to writing this letter, Paul has been travelling and announcing this new creation, evidenced by the formation of the new family, among people who are not Jewish; including the people of Galatia (part of Modern-day Turkey).

These Galatians originally heard this announcement because of Paul and they embraced it.

But, as Paul continued his travels, leaving them behind, some other Jewish Christians had arrived. We’ll talk more about them in a couple of weeks. But, in Paul’s absence, they have been telling these non-Jewish believers that they need to become Jewish to be part of Abraham’s family.

Paul is furious.

And while it is true that the Galatians are being tempted to exchange identity based on God’s grace for one based on human effort and religious status—an issue Paul will take up—his anger is deeper than this issue.

Because to return to performance-based religion or ethnic boundaries or cultural conformity is more than the problem of “faith versus works”, it is a total abandoning of the very reality of God’s new world, initiated in Christ and lived out in community.

As someone else has put it, ‘[for a Gentile] to get circumcised would therefore be to deny that the new thing had happened.’[xiv]

Paul states, rather boldly, this isn’t just a different version of the gospel—it is no gospel at all. It is a muting of an announcement. It’s a public denial of God’s act of redemption. To believe this ‘no gospel’ is to is to walk backward into Egypt when the Exodus has already begun.

Using even stronger language, in verse 7, Paul calls it a perversion. The Greek word he uses is metastrephō, and it literally means to turn something into it’s very opposite, ‘a turn from light to darkness.’[xv]

This ‘no gospel’ is akin to turning the lights off. It’s not so much a turning the volume down on a radio; it’s pulling the radio’s plug out of the wall.

To drop in another iconic movie quote, ‘What we have here is… failure to communicate.’[xvi]

The people teaching this garbage were not denying Jesus’ death and resurrection, as such, but they we’re missing the implications of it entirely.[xvii]

And, in embracing this trash, the Galatians would be a silencing the announcement that God’s Kingdom has begun. If there’s no new family, there has been no new creation, and therefore the old order is all there is.

It’s a total misalignment of who you are and what story you belong to. This “different gospel” being presented is not just an alternate theology—it is an identity-shaping distortion.

FITTING OUT

Of course, we must ask, if this is ‘no good news’ at all, why believe it? Why would these Galatians, these Gentile members of God’s new family even be suckered into it?

Well, let’s consider what was at stake for Paul’s Gentile converts.

In the Roman Empire, religion and public identity were deeply intertwined. Religion was not a private affair—it was civic duty. To be considered a good Greco-Roman citizen, you were expected to worship the gods of your cities, households, and most importantly, to honour Caesar as “lord” and “Son of God”. No matter where you shopped, where you played, where you worked, and where you ate—the worship of the gods was unavoidably involved. Sacrifices and festivals weren’t just spiritual events, scattered throughout the year; they were daily public expressions of loyalty recuring throughout the day.

To reject the gods, to abandon honouring them or refusing to offer a sacrifice on behalf of Caesar was to reject your city, your people, your country.

To stretch for a modern equivalent: it would be like burning your nation’s flag in a public square. But then again, this still doesn’t come close enough.

To walk away from idol worship wasn’t just about abandoning a belief system. It meant risking economic ruin, social exclusion, even violence.

Now, Jews were allowed to opt out.

Understandably, rightly, they refused to worship any other god’s but the One true God. And within the Greco-Roman world they were viewed as very odd for denying all these other god’s—in fact, a Roman nickname was coined for them, and nickname that was also later applied to Christians: Atheists.

As an aside, if you call yourself an atheist, you have the God of the Bible to thank for that!

Despite being treated as social oddities, the Jewish people did have an official exemption and legal protection. Avoiding a history lesson, Rome tolerated Jewish monotheism—strange as it seemed—because it was ancient and rooted in tradition.

But Gentile Christians didn’t have this privilege. They had no such protections. They were abandoning the gods of their birth, turning their backs on Roman expectations, and aligning themselves with a crucified Jewish Messiah.

To become a Christian was to reject idol worship and the pantheon of Roman gods—the very gods that undergirded one’s trade guild, neighbourhood festivals, and civic life.

Christians refused to participate in the sacrificial systems at the marketplaces and at their dinner tables. They didn’t go to the temples. They didn’t bow down to images. They called Jesus “Lord” instead of Caesar. And they welcomed the poor, the marginalized, even slaves—into one family. These Gentile believers were leaving behind their inherited cultural identity, and they had no ethnic protection.

They do not fit in.

This made them strange. Deviant—to use a word that was often thrown at them. Suspicious. Unpatriotic. Potentially subversive. Vulnerable—socially, economically, politically, and even physically. [xviii]

To ease the problem, the Galatians could, of course, just go ahead and carry on worshipping all these false gods and just added Jesus to the list—‘one among the many’. No one at the time would have minded this at all. However, this runs against the grain of the gospel’s proclamation; it is incompatible with the message of the One true God to whom all glory is due. Paul, in his wonderful approach, has to tackle this in his letter to the Corinthians—but this doesn’t seem to have been an option that the Galatians considered as viable.

Of course, there was another way. And it may seem odd to us, but, by undergoing circumcision, these Gentile believers could change their legal ethnicity.

So, when Jewish-Christian missionaries, for their own reasons, came to the Galatians offering a way to “complete” their faith by adopting the law—by becoming circumcised, observing Jewish calendar and kosher laws—they were offering a way out of the cultural tension. A way to gain legal recognition. A way off the radar.

For many Galatian believers, the temptation of adopting Jewish customs wasn’t just about theology—it was about survival. If they could be seen as a subset of the Jewish people, perhaps the pressure would ease.

I’m sure Paul understood the temptation—he’s been on the receiving end of persecution, too. His body bore the marks of following Christ.[xix] But he sees this move clearly for what it is: a step backward into a world that no longer defines the people of God. It means muting the announcement of God’s new creation.

In a wonderful, animated film called Home, there’s an Alien called Oh!, part of a race known as the Boov. Among his own kind, Oh! laments, ‘I do not fit in. I fit out.’

For anyone who has followed Jesus for any length of time, I think we can all relate to this sentiment.

None of us really want to ‘fit out.’

And yet, as Paul rightly sees it, this fitting out is where our faithfulness grows and where the announcement of God’s new creation is proclaimed.

It’s only in ‘fiiting out’ that we can operate as ‘salt’ and ‘light’, as a ‘royal priesthood’, to use other New Testament descriptions of our role as God’s portable presence within the world. As salt we preserve and enhance the world around us, as light, we radiate God’s truth and love to others.

But, as Oh! recognised, ‘fitting out’ is uncomfortable, vulnerable, precarious even.

Paul is not offering a gospel that is convenient. Paul is not a people-pleaser (v.10). He is offering the more difficult path—the path of hardship, tension, and often ostracization.

By contrast, what this faction is offering is the people-pleasing path. It’s the path of least resistance—the path of cultural accommodation. ‘Just get circumcised,’ they whisper, ‘and you’ll fit in better.’ It is compromise dressed in the robes of piety.

This temptation is not ancient history. Karl Marx famously called religion the “opium of the masses”—a way of numbing ourselves to the pain and tensions of the real world. And sometimes, we still want Christianity to function that way. We want it to be uncomplicated.

Even today, the ‘people-pleasing’ preachers, leaning on all manner of false calls to piety, lure us out of the tension of our vocation. And so, today, we have those who tell us to ‘come out of the world, withdraw, have nothing to do with it’, on the one side, and those who call us to ‘be in the world, warring against it’, on the other.

But the gospel Paul defends—the gospel of the crucified and risen Messiah—is neither. Rather, the harder road is to be an expression of God’s grace and peace within the world. It’s about loving engagement and faithful presence. It’s about living in the old, being an exhibit of the new.

That’s not simple.

It’s not pain-free.

Especially when other Christians, behind their theological barricades, on either side, take aim at us for not committing to the so-called “faithful”. Add to this the exclusion and ridicule we receive from the world at times, and the violence Christians today experience in parts of the world, and the sense that we don’t belong, that we ‘fit out’ is hard to bear.

But this tension is the lived reality of our Christian identity—part of what it means to carry our cross, I suppose.

Paul’s message to the Galatians is still urgently needed today. We, too, are tempted to turn to “other gospels”—gospels of performance, of comfort, of cultural accommodation. We are tempted to define and clothe ourselves with nationalism, achievement, heritage, or even religious legalism.

All of these things are all ways of easing the pressure, of shirking the responsibility of straddling two worlds.

Galatians is not just a theological argument. It is a call to courage. A call to fidelity. A call to embrace the hard, beautiful, transforming work of being God’s new creation in the midst of the old world.

Of being loyal to the new, and loving the old into the new.[xx]

The kingdom of God is here—you’re it! But the tension is real. Paul’s call still echoes:

Don’t desert the one who called you by the grace of Christ.

Don’t trade the gospel for something more comfortable.

Don’t forget who you are.

Don’t settle for a lesser identity.

You are part of God’s new creation.

So live like it.

Let the announcement of the graceful and peaceful reign of the One who redeems and forgives, be declared through your life.

‘“You are the light of the world—like a city on a hilltop that cannot be hidden.”’

—Jesus, Matthew 5:14 (NLT)

Reflection Questions:

- Where do I feel pressured to conform to the values of the “present evil age”?

2. In what ways am I tempted to build my identity on something other than Jesus?

3. How can I show Spirit-empowered love across ethnic, cultural, or social boundaries this week?

4. As ‘salt’ and ‘light’, how am I preserving and enhancing the lives of those around me? In what ways am I reflecting God’s light to others?

5. How do you think the “gospels” of performance, comfort and cultural accommodation distort our identities?

ENDNOTES AND REFERENCES:

[i] T. S. Elliot, The Dry Salvages, III, Four Quartets (Faber and Faber, London, 1983), p. 36

[ii] In addition, maybe we have also reduced the focus of the reformer, Martin Luther’s debate, too. As Nijay Gupta comments, in his reading of Luther, ‘[I] think many interpreters of Luther have assumed the German Reformer focused on “justification by faith” as opposed to “justification by works.” I believe this is only partly true. Luther was against any system of theology that tried to master God, put God in a box, or put self above or in the place of God. In fact, I think Luther would be disappointed to see today that he was being associated primarily with the idea of “justification by faith.” Why? Because his passion was not for the doctrine of justification of faith (or any other doctrine); he was focused solely on the person of Jesus Christ. For Luther, faith meant clinging to Christ for righteousness, life, and salvation. This is important to point out because in that sense, faith is not the opposite of work. It is not the absence of something. Rather, faith is the active, engaged, and attentive reliance on God through Christ, just as Paul writes that what really matters is “faith working through love” (5:6 NRSV). … [Faith] represents a living and active relationship, where we trust Christ in all things by the power of the Spirit.’ [Nijay K. Gupta, Galatians: The Story of God Bible Commentary (Zondervan Academic, Grand Rapids, Michigan, 2023), p.14]

[iii] Michael J. Gorman, Apostle of the Crucified Lord: A Theological Introduction to Paul and His Letters, 2nd Edition (Eerdmans, Grand Rapids, Michigan,2017), p. 218. As referenced in Nijay K. Gupta, Galatians: The Story of God Bible Commentary (Zondervan Academic, Grand Rapids, Michigan, 2023), p.6

[iv] As Eugene Peterson notes, Paul’s favourite words ‘for this great, all-encompassing truth about God’ is gospel. Good News. Evangellion, in the Greek. In his writings, Paul uses this word more than sixty times. By comparison, ‘Mark only uses it seven times; Matthew, four; Luke, twice; and John, once.’ [Eugene H. Peterson, Travelling Light: Meditations on St. Paul’s Letter of Freedom (Helmers & Howard, Colorado Springs, 1988), p. 37]

Paul has two important sources for this word.

Firstly, the inheritance of Isaiah. Isaiah, for example uses the Hebrew equivalent to speak of the ‘Good tidings (news)’ that the Lord is coming, in all his glorious power, to rule with awesome strength and to carry and feed his flock (Isa. 40:9-10, a passage of Scripture that Mark quotes at the beginning of his gospel, too.)

Secondly, it should also be noted that in Paul’s day, the term Evangellion —“gospel”—was not a Christian word. It was a Roman one. It was used to announce the birth or victory of the emperor. The Roman imperial cult proclaimed that Caesar Augustus was the “son of god” who brought peace and prosperity to the world. His reign was the “good news.”

So when Paul uses the term gospel, he’s not just talking about personal salvation. He’s offering an alternative public announcement. He’s saying: the true Son of God is not Caesar—it’s Jesus. The true peace does not come from imperial conquest—it comes from the cross.

Neither of these sources, for Paul, are contrary nor irrelevant. As Craig Keener says, ‘Paul undoubtedly inherits the term “gospel” from prior Christian usage, but like his predecessors, he also derives it from Isaiah.’ [Craig S. Keener, Galatians: A Commentary (Baker Academic, Grand Rapids, Michigan, 2019), p. 61]

[v] For example, 1 Thessalonians 4:13-18; 1 Corinthians 15:51-58; Romans 8:15-25

[vi] 2 Corinthians 5:17

[vii] Galatians 5:1

[viii] My paraphrase of Philippians 3:20

[ix] As an aside, Paul also had ‘Roman’ citizenship—something he never denied and used to spread the announcement of the Kingdom. One of the reasons he goes by the name ‘Paul’, is that it is the Romanisation of his Hebrew name, Saul. Though in no way denying his Jewish ethnicity, Paul was happy to be known as Paul in his outreach to non-Jewish peoples’

[x] Ephesians 3:10-11

[xi] The Greek term pistis, often translated “faith,” carries the connotation of faithfulness or loyalty.

[xii] Galatians 5:6

[xiii] Galatians 6:6

[xiv] N. T. Wright, Commentaries for Christian Formation: Galatians (Eerdmans, Grand Rapids, Michigan, 2021), p. 33 (Italics original)

[xv] Nijay K. Gupta, Galatians: The Story of God Bible Commentary (Zondervan Academic, Grand Rapids, Michigan, 2023), p.7

[xvi] Cool Hand Luke (1967) – again, for those counting, that’s 58 years ago!

[xvii] As Keener states it, ‘It is doubtful that Paul’s rivals were denying Jesus’ death or resurrection, which seems not to have been at issue in Galatia. Paul did insist, however, that they were missing the theological implication of those events: if Christ died “for our sins” (1 Cor. 15:3), he did so to free us from the present evil age (Gal. 1:4). The law proclaimed by Paul’s rivals, by contrast, lacked this power (Gal. 3:21-22). Christ was exclusively sufficient.’ [Craig S. Keener, Galatians: A Commentary (Baker Academic, Grand Rapids, Michigan, 2019), p. 62]

[xviii] For some great books on this, see: Larry W. Hurtado, Destroyer of the Gods: Early Christian Distinctiveness in the Roman World; Mary Beard, John North and Simon Price, Religions of Rome: Volume 1, A History.

[xix] Galatians 6:17

[xx] At this point in my sermon, I felt led by the Spirit to share extra words regarding the choices I feel lay before us in this current climate. You’ll have to watch our YouTube video for these words (the link was at the beginning of this blog).

Leave a comment