THEME: The Story of the God who Seeks

Here’s my longer notes from this morning’s @mccbury service (17th August, 2025), continuing our FREE TO GOD series which explores Paul’s letter to the Galatians.

To be honest, it’s been a tough one to prep this week, and something I’ve re-written and re-ordered several times. I trust this makes some sense, as I try and hit a very important conclusion.

You can also catch up with this via MCC’s YouTube channel (just give us time to get the video uploaded).

‘God is whoever raised Jesus from the dead, having before raised Israel from Egypt’

—Robert Jenson[i]

READ: GALATIANS 4:8-20 (NIVUK)

DO YOU HEAR WHAT I HEAR?

‘It all sounds the same, doesn’t it?’

I’ve been saying this a lot recently.

Only this past week, in fact, I found myself chatting with someone of the same generation as me, having one of those conversations where we put the world right as we bemoaned and grieved over the state of modern music.

We are both fans of the ‘seventies’, ‘eighties’ and ‘nineties’, who also enjoy the rock and roll sounds of the ‘fifties’, and who both agreed that (with the exception of the ‘eighties’) nothing comes close to the peak that is the ‘sixties.’ There is so much variety in those eras; you can keep on listening and never get bored.

‘But with today’s music,’ we both wailed, ‘well, it all sounds the same.’

This certainly isn’t the first time I’d made this remark. I have a long-running joke with my son, Corban; whenever we’re listening to the car radio and a modern song comes on, I’ll attempt to guess the artist. If it’s a female vocalist, I’ll jokingly ask, ‘Is this Taylor Swift?’ If it’s a male, ‘Is this Ed Sheeran?’ I can’t tell. ‘They all sound alike. There’s no originality,’ I’ll say.

Occasionally, I have even uttered those condemning words of, ‘It’s not even music … it’s just noise!’

I have turned into my late dad. And this alone should start the alarm bells ringing, telling me I should know better. Because my dad (like all our dads, I suspect) made the same error in judgement about the music I listened to as a teenager.

I was a big rock fan as a kid. I still am. To my dad, though, it was all noise. He never appreciated the difference between hard rock and heavy metal. He confused Indie with Heartland rock and Grunge. I could never get my dad to appreciate that Nirvana were not akin Bon Jovi, who were nothing like U2, who were a world apart from Blur.

I should know better.

I’m also a fan of classical music, and it pains me when I hear people say that it all sounds the same. Yes, from a distance, if you refuse to listen closely and consider the distinctive melodies you will wrongly presume that Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov sounds the same as his student, Igor Stravinsky. But they’re as different to each other as Rachmaninov is to Tchaikovsky.

From my own experience, I should know better.

The problem is not the music (although I struggle to admit it). The problem is that, like my dad, and like those who criticise Classical music, I am just not paying enough attention to recognise the crucial, all-important variations.

Corban, who is a fount of knowledge on modern music, reliably informs me that it doesn’t all sound the same. In the world of Hip-Hop, for instance, you should never confuse your Crunk with your Drill, or your Grime with your Trap. Pop rap, Comedy rap and Boom Bap are not the same. And only a fool would hear G-funk and mistake it for Bounce.

When it comes to Pop music, past and modern, Bubblegum Pop has always been a valid alternative to Alternative Pop. And Synth Pop, Wonky Pop, Art Pop and Schlager all have their own sound.

It’s not just noise. It doesn’t all sound the same. I’m just ignorant, and in my senior years, I’m just, wrongly, too comfortable in that ignorance.

People do the same thing with religion.

‘It’s all the same,’ they say. I used to say the same thing. ‘They all talk about prayer, worship, festivals, ideas about the divine, right and wrong, etc., so they’re all the same; all much of a muchness.’

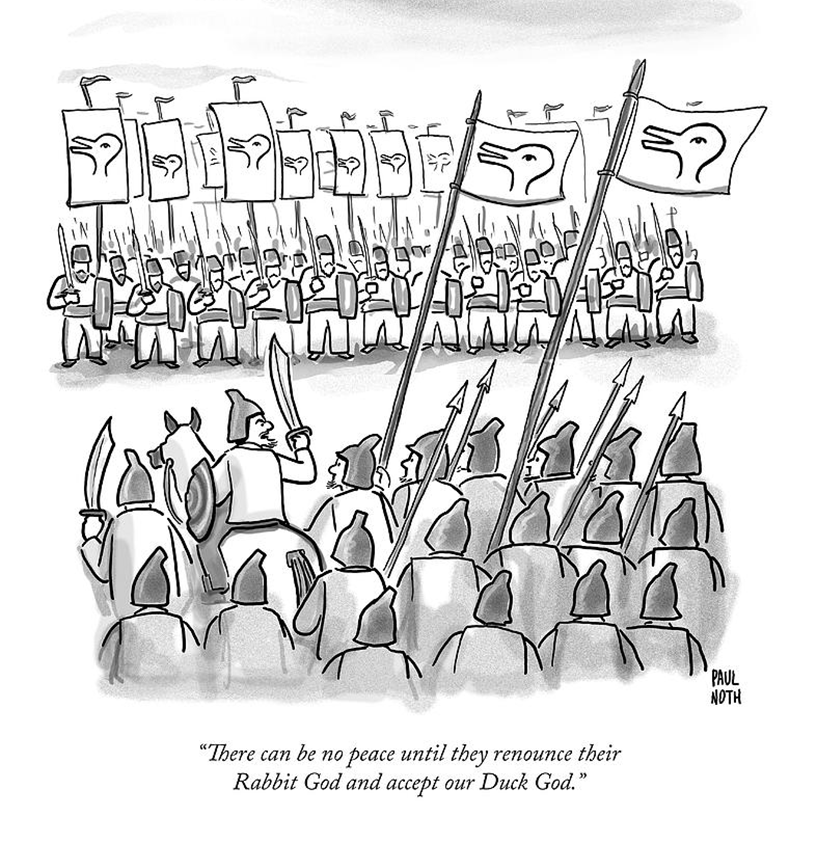

I remember seeing the following cartoon many years ago.

To be fair, I too find religious violence to be both ridiculous and repulsive, so I get the humour and the sentiment. It’s a good cartoon. Yet, it plays on the idea that all religions are the same, which is not true.

All such statements do is reveal our ignorance and our unwillingness to lean in and listen carefully.

Whether it’s music or religion, there’s an innate danger to our ignorance: that if you see it all as the same then you will handle it all in the same thoughtless way.[ii]

This is Paul’s concern in what we have read.

CALENDAR GODS

In verses 8 through 10, Paul clearly states that not all religions are the same as he reminds the Galatians:

‘Before you Gentiles (non-Jewish people) knew God, you were slaves to so-called gods that do not even exist. So now that you know God (or should I say, now that God knows you), why do you want to go back again and become slaves once more to the weak and useless spiritual principles of this world? You are trying to earn favor with God by observing certain days or months or seasons or years.’

(NLT)

‘I fear for you,’ Paul goes onto say.

It’s a pretty blunt passage: Paul wastes no time is stating something that I imagine he had stated to these Galatians when he was physically with them, teaching them. In a nutshell: your old ideas of what religion is all about, along with the gods you used to worship, were all wrong. Your whole belief system was messed up and it messed you up, too.

You were slaves to gods that don’t exist, he says.

Plus, you were slaves to ways of knowing those gods that are weak (ἀσθενῆ, asthenēs) and worthless (πτωχὰ, ptōchos).

Paul chooses to point this out by talking about the calendar.

Every ancient culture had a calendar.

Now I know what has just happened—you heard me say calendar, and instantly in your head, because you recognise the word, you’re probably thinking of the calendars we have; those things that are basically a book that we hang on a wall, and that help us mark off birthdays, anniversaries, dentist and doctor appointments, and alike. Our calendars also usually have photographs of nice scenery, or pictures of puppies and ducklings, or our fav’ pop stars like Taylor Swift and Ed Sheeran.

But this is not that.

For starters, ancient calendars were not books hung on walls. People didn’t do that back then. Although, every town or city would have someone or some people whose job involved reminding everyone of what specific day, month, season or year would be approaching.

Not because of people’s birthdays or dentist appointments.

But because, in the ancient cultures, days and months and years were intimately tied into religious ideas about the so-called gods and how the world worked.

For example, some days were seen as unlucky: days when you should avoid journeys or forming business contracts. Like how some people today, I suppose, view Friday 13th. Except, in Greco-Roman times, even-numbered days were treated as unlucky, and odd-numbered days, and even rituals involving odd numbers (like saying a prayer or incantation three times) were seen as granting more chances of success.

One Roman writer talks about how some people, in Rome, had a custom of only cutting their fingernails on market days, before going on to mention that some also only cut their hair on the 17th or the 29th day of the month (apparently, it prevented hair loss and headaches).[iii]

But outside of the day-to-day issues of business and personal hygiene, there was a strict set of timetables for festivals, all of which were consecrated to numerous so-called gods. Failure to attend to these festivals, or even to celebrate them on the wrong day, in the wrong place, at the wrong time, in the wrong way was to court with disaster.[iv]

The gods of the ancient world were fickle; prone to having what we would call ‘bad hair days’ over little things. In the ancient world of Greece and Rome, ‘most people did not see their gods as models of virtue to emulate … the average person on the street just wanted to avoid their wrath.’[v] The average farmer just wanted to make sure they’d have a good harvest and avoid droughts and famines. The average city wanted to avoid war and disease.

The calendar was, in their thinking, the way to navigate all this danger.

It was fuelled by fear and superstition. I’m saying that as if they’re two separate things, but superstition is, to be blunt, a fear-filled practice. The ancient thinking—like the thinking of those who avoid cracks in pavements in our day—is all an attempt to be in the right place, at the right time, doing the right thing to avoid a bad thing from happening.[vi]

Underpinning all of this, is the fundamental and enslaving idea that the gods don’t seek us, the gods don’t know us; it is human activity that ‘draws to us’ or ‘diverts from us’ the attention of the gods.

Whether it was seeking their favour or seeking to avoid their tantrums, the seeking was always, solely, a one-sided, human-driven enterprise.

Before coming to know Jesus, the Galatians have grown up in this culture: their ears have been saturated with thousands of Greek and Roman religious sounds since childhood. Their ears are attuned to a particular religious approach; a particular way of knowing the gods.

They hear talk of a ‘calendar’, with it’s mention of days and years, and they colour in this concept with their cultural ideas.

And Paul is concerned about this.

We’ve talked a lot, in the previous weeks of this series, about Paul’s concern that these non-Jewish Christians are being pressured by Jewish Christians to become Jewish: to be circumcised, if your male, and to adopt the Law of Moses. The argument of these false teachers has basically been, ‘You a not genuine believer in God, a genuine part of God’s family, until you do.’

Paul, as a circumcised Jew, has been strongly arguing against this.

His main argument has been that, because of Jesus, non-Jewish believers do not need to become Jewish in culture and custom to be a full and equal participant, an equal heir in what God has now brought about through Jesus’ birth, life, death and resurrection.

But Paul’s not just annoyed with the threat of circumcision. As verse 10 seems to indicate, it seems that some of the Galatians have already begun to adopt the Jewish Calendar. Furthermore, they are misusing it.

THE GOD WHO SEEKS

The Jewish people also had a calendar—festivals and special days that were prescribed by the law of Moses, celebrations that took place each year at certain times.

But these things, though they may sound the same to the untrained ear, were not the same thing as the calendar of Rome or Greece.

As mad as this sounds to suggest, considering what we have said so far in this Galatian journey, if a non-Jewish person wanted, of their own voluntary desire, to celebrate the Jewish Passover, say, I don’t think it would have bothered Paul.

Paul’s pastoral posture is flexible when it comes to rituals. In his letter called Romans, written to a mix of Gentile and Jew, he says it’s a matter of individual choice.[vii] As a Jew himself, Paul is certainly not anti-ritual or anti-festival in his own practice, as seen in various places in the book of Acts.[viii] But Paul is not legalistic, either. Nowhere does Paul say Christians must partake in these things.

Based on this, I’m going to suggest that Paul is not worried about the Galatians showing an interest in Jewish holidays. As he says in verse 18, ‘It’s wonderful that you are keen to do good.’

Rather, the problem Paul has is that a), they’ve been forced to adopt it and, b) even worse, that the Galatians have picked up Jewish Calendar and are treating it with the same superstitious motives they had toward their old religious calendars, as if the Jewish calendar is about humanity finding God.

The Jewish festivals are certainly not about people finding God, nor are they about staying on God’s good side. Rather, they are all acts of remembrance—remembering how God found us.

Passover is about God’s rescue.

The Festival of Tabernacles (Sukkot) is about God’s provision.

Pentecost (Shavuot) is about God giving Torah.

Sabbath has nothing to do with us doing anything for God, it’s God doing something for us.

Are you catching the drift, here?

The Jewish festivals tell a radically different story, and the Galatians are at risk of missing it.

In the ancient world, there’s nothing like the story of the Old Testament, the story of the Hebrews and their encounters with God.

I’m not going to give a history lesson, but I’ve spent a lot of time over the past couple of years reading a lot of ancient stories, and the God that appears consistently throughout the story of the Old Testament is very odd in comparison to the stories of all the other so-called ‘gods’.[ix]

I could give several examples.[x] But, to boil it down to one fundamental difference: Nothing in the story of the Scriptures is about how we ‘get to God’ or how we find “god”. Instead, it is about how God has come to us, how God saves us, how God redeems and repairs us.[xi]

As one wonderful Jewish writer of the last century described it, ‘God is pursuing man … All of human history as described in the Bible may be summarized in one phrase: God is in search of man.’[xii]

In the story of scripture, God is actively searching for humanity—entering history, revealing Himself and inviting participation.

The very first question God asks in the Bible is, ‘Where are you?’[xiii] and it’s a question that rolls on through the rest of the story.[xiv]

Again and again, and again, as the words of Psalm 23 tells us, God’s goodness and unfailing love run after us, pursuing us.[xv]

To get back to Abraham’s story—a story Paul is keen for us to remember in Galatians; we never, in all of Genesis, learn how Abraham, amid his ancient Sumerian culture, “discovered” God. The story never says that Abraham finds God. Rather, all we are told is that God called Abraham and Abraham responded.[xvi]

Abraham’s knowledge of God begins with God’s self-revelation and God’s knowledge of Abraham.

When put this way, faith is not a superstitious thing: it is not some signal we send up, hoping God will respond. Faith is not some effort on our part to shout as loud as we can or move in a timely way to get God to know us. Faith in God is a response to God’s question, call and movements toward us.

Our knowledge of God is not based on, and nor does it begin with, our attempts to figure God out.

As Paul said to the Galatians, it’s not so much that we found God—though there’s nothing wrong with such language. But the more foundational truth is, that God found us.

This is the truth of the story of scripture, in both the Old Testament and the New.

In the Old Testament, the crucial chapter demonstrating this searching action of God, a chapter that proves to be a pivot point that is echoed throughout the canon, is the Exodus story. God enters history and rescues the Hebrews from enslavement, both physically and spiritually.

The prophet, Ezekiel, many years later, leans into the Exodus story and poetically relays how Israel was like an unwanted child, abandoned by all others and left naked and desolate. Until God walked along, finding the child in its bloody, helpless and lost state. God took up the child, wrapping it up in his own cloak, washing it clean and claiming it as his own. (Ezekiel 16:1-14)

In the New Testament, as in the Old, God enters history, revealing himself. The purposes are the same: to draw humanity up into his cloak, to bathe us and adopt us as his own. But this time, once and for all time, God becomes one of us, dwells with us, serves and teaches us, dies for us and is raised for us, to rescue us.

Jesus, when speaking of his own mission, saw seeking as its core: ‘For the Son of Man came to seek and save those who are lost.’ (Luke 19:10, NLT)

The ‘Old’ and the ‘New’ are not two differing stories about two differing Gods, as some second century writers tried to make us believe.[xvii] The New Testament is the climax to the story of this ancient pursuit of the eternal God.

As someone else wonderfully worded it, ‘God is whoever raised Jesus from the dead, having before raised Israel from Egypt.’

The testimony of the Jewish story, as laid out in the Old Testament, and as seen in its climax in the Gospel of Jesus, is that our knowledge of God begins with who God has demonstrated himself to be through his acts in history.

The story is vital.

Again, Paul doesn’t have an issue with calendar; with Passover, et el. There’s nothing wrong with rituals, as such. It’s how we use them. At their best, rituals are how we look back on God’s story: how we remember that story and how we retell that story to the next generation.[xviii]

We did a series earlier this year on Rhythms, habits … rituals really—like prayer, scripture, fasting, silence. None of these things were about superstition or catching God’s attention. They are all about sitting in awe of God, soaking in the story of what God has done for us, allowing that story shape our identity.

Instead of a faith rooted in superstition and rites driven by fear, we have a faith—a living and loving trust—that has been created and is continually nurtured by awe and wonder in what God has done.

Paul does not want the Galatians to hear this story and handle it, thoughtlessly, like everything else they have heard or seen.

If they don’t recall this story, they risk caving into the pressure religious legalism.

If they don’t remember this whole story, their faith practice risks becoming skewed by superstitious nonsense.

Paul, in a word, wants their faith to be anchored in the story of God, not superstitious speculation.

ROCKETS OR ROOTS

The same is true for all of us.

God’s story, the scriptural story, is vital to me and to you.

I’m saying this, not because we are at risk of being superstitious about it like the Galatians. Although, sadly, some people do get superstitious.

I’m saying this, because I think it’s worth pointing out the often-overlooked obvious lesson of the letter of Galatians: that knowing the story of the Scriptures, what we now call the Old Testament or the Hebrew Bible, is essential.

Zoom out of the letter a little and consider all we have read in the past weeks as we have travelled through this letter.

This letter is full of illustrations from Genesis; Paul oftens alludes to the Exodus story in his language of rescue and in his conversation about the temporary guardianship of the Jewish Law; within his own testimony, Paul has echoed the words of the prophet Jeremiah, and his personal journey has contact points with the stories of both Moses and the prophet Elijah; Paul has even cited from the daunting texts known as Deuteronomy and Leviticus (and will do so again); he’s even quoted from an obscure, tiny text called Habakkuk.

Paul’s not referring to these Scriptural sources so the Galatians will just pass them on, in parrot fashion, to the false teachers. Paul has been appealing to a story he taught the Galatians when he was visiting them. It’s why Paul fears that all his hard work among them has been for nothing.

To be clearer: Paul expects the Galatians, who are not Jewish, to know this very Jewish story, and to see this story as foundational to their own story, even though he does not expect them to come under Jewish law.

I shouldn’t really have to spell this out, but I will: When Paul talks about ‘God’ he is not talking about some generic idea of God—as if God is a blank outline that we get to colour in however we please. Paul has been more than clear: The God who has fulfilled his promises through Jesus, is the same God who gave those promises to Abraham in the first place.

Sadly, on occasion, people have read Paul’s letter to the Galatians, heard his desperate plea that these non-Jewish people should not come under Old Testament law, and then wrongly walked away presuming that what Paul means is have nothing to do with the Old Testament story whatsoever.

But Paul is not questioning the legitimacy or importance of the story of what we call the Old Testament.

To point out the bloomin’ obvious (as my late engineering teacher would say), Paul’s whole argument of what Jesus has achieved rests on an understanding of the Hebrew story.

Yes, as Paul has said throughout this letter, and as I made clear (I hope) in the first week of this series, because of Jesus, we are in a whole new era of history.

However, the Jewish story behind Jesus is not like rocket boosters that launch spacecraft into orbit. Those of you who have seen launches know what I mean: When the space shuttle escapes Earth’s gravitational pull, the rocket boosters are no longer needed and detach, falling back to earth. That’s not what this is.

As someone else brilliantly described it, the biblical story is more like a tree. ‘We now enjoy the spreading branches and abundant fruit in its New Testament fulfilment. But the Old Testament is like the inner rings of the trunk—still there, the evidence of a history long past, but still the supporting structure on which the branches and fruit have grown. The relationship is one of organic continuity, not ruptured discontinuity and abandonment.’[xix]

You can’t lop Jesus off from the rest of the story and stick him in as the conclusion to a whole different story.

It would be like taking the end of the film Saving Private Ryan and sticking it to the beginning of Pirates of the Caribbean. Neither story would make sense of the other.

Sadly, it’s been attempted. I don’t mean with the movies. There have been plenty of attempts, by Christians, to pull the story of Jesus out of the grand narrative of the Bible.

And as the Scottish minister, T. F. Torrance put it, ‘Whenever the church has been tempted to tear Christianity from its God-given roots in Hebraic soil it has destroyed something so essential that its effects bear strange fruit for centuries afterwards.’[xx]

I’m not going to bore you with examples.

But legalism and superstition always sprout up when someone cuts something out of the story, or when someone cuts something away from the story to stand apart on its own.

Cults happen when there’s an emphasis on one verse, ripped away from the movement of the narrative.

Bloody and barbaric crusades arise when the story is bent out of shape and something other than Jesus is made as the climax of it.

Great injustices transpire when the Bible is atomised into detached, free-floating verses like a ‘deconstructed cheesecake’, and we cease to chew them over as ingredients of the story of God’s faithful and redeeming search of humanity.

There are two wrong approaches to the Old Testament. To use Torrance’s picture of Jesus sitting, like a plant, in the soil of the Hebrew story:

One wrong response, like the legalists Paul is dealing with, those who want to see the Galatians circumcised, is to pretend nothing new has come, nothing new has happened, and bury the new beneath the soil of the old.

The other wrong approach, that modern readers of this letter are at risk of doing, is to pull Jesus out of that soil and stick him elsewhere or just leave him drifting, unrooted to anything.

We are called to neither posture.

To be sure, there are parts of the Old Testament I struggle to read and there are passages I certainly struggle to make sense of considering the cross of Christ. And, I need to add, how we read that story in light of Jesus is equally as important as reading it. But I cannot agree, based on the New Testament, with any suggestion that we should ‘have done’ with the Old.

I live in the new thing Jesus has done, but I need the older story in order to understand the new thing, and I need the whole story to understand God’s story, my story and the story of the world.

‘“Your mistake is that you don’t know the Scriptures, and you don’t know the power of God.… haven’t you ever read about this in the writings of Moses, in the story of the burning bush? Long after Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob had died, God said to Moses, ‘I am the God of Abraham, the God of Isaac, and the God of Jacob.”’

— Jesus, Mark 12:24, 26b-c (NLT)

ENDNOTES AND REFERENCES:

[i] Robert W. Jenson, Systematic Theology, Volume 1: The Triune God (Oxford University Press, USA, 2001), p.63

[ii] As an aside, I’m reminded of the film Minority Report and the “pre-cog”, Agatha’s consistent call of, ‘Do you see?’, to Tom Cruise’s character, John Anderton. I’m not going to give an overview of the film, but in brief: the film is based around Philip K Dick’s novel and the idea of seeing the future to predict a crime, allowing the police to arrest people before the crime is even committed. Knowing this system, someone commits a crime in a way that resembles another crime, in the knowledge that the vision of this crime will be labelled as an echo of a previous incident and ignored. Only by looking close enough, can John Anderton approach it differently.

[iii] Pliny the Elder (circa 23-79 AD), Naturalis Historia (Natural Histories), Book 28.V.28. Chapters III-V, of Pliny’s work, are full of stock examples of Greco-Roman superstitions.

[iv] Craig Keener’s commentary on Galatians provides plenty of references in the footnotes to ancient writers on the importance of certain days, seasons and years: Galatians: A Commentary (Baker Academic, Grand Rapids, Michigan, 2019), pp. 359-364]. Also, Mary Beard, John North and Simon Price’s, Religions of Rome: Volume 1, A History provides plenty of discussion on the importance and continuing development of the Roman ‘calendar’.

[v] Nijay K. Gupta, Galatians: The Story of God Bible Commentary (Zondervan Academic, Grand Rapids, Michigan, 2023), p.177

[vi] As an aside, the Greco-Roman culture thought this was rational and therefore, because it was also based on tradition, they hailed it as Religio. Foreign practices that didn’t acknowledge this and whose practices seemed erratic and undisciplined were labelled as irrational. And, if they dared suppose themselves to be superior to what was considered rational, even going as far as questioning the existence of the gods and the structure implemented to appease them, they were labelled Superstitio. The Jewish belief system, because it was considered ancient in its culture was treated with some legal protection, to an extent, by Rome. But, it was still disdained and seen as superstitious in comparison to the rites of Greece and Rome. Christianity, when it emerged as an offshoot of the Jewish way, was treated with utter contempt and had no legal protection and was labelled Superstitio from the outset. No Greek or Roman non-Christian writer speaks favourably about Christianity in the first three centuries, at least (and generally because of the values systems that have been cherished in modern society: care for the poor, justice, equality under God, the sanctity of human life, etc) . Both ‘Judaism’ and ‘Christianity’ were labelled as atheistic for denying the gods. What is fascinating, is that in a few sentences in Galatians, Paul has masterfully flipped the cultural perception on its head: What Israel’s God has achieved and the life that summons us to is religio. Whereas what Greek and Rome have practiced traditionally is mere superstitio.

If you are interested to learn more: Mary Beard, John North and Simon Price’s, Religions of Rome: Volume 1, A History provides some great insights, as does Larry Hurtado’s Destroyer of the Gods: Early Christian Distinctiveness in the Roman World. Equally, and for a more panoramic view of how Jewish and Christian values have shaped our culture, Tom Holland’s Dominion is masterful and accessible, and so is Glen Scrivner’s The Air We Breathe: How We All Came to Believe in Freedom, Kindness, Progress, and Equality.

[vii] See Romans 14:5-6 for example, where Paul says that observing days of not observing them is something for an individual Christian to decide as a matter of their own discipleship. Keener (Ibid, note iv) also correctly notes that, ‘Certainly [Paul’s] churches knew about festivals (1 Cor 5:7; 16:8). In the earliest centuries, Christians depended on Jewish determinations for Passover to set their own calendars for Easter.’ Also, as evinced in Acts and some of Paul’s other writings, ‘The Lord’s Day/The first day of the week’ (Sunday) had significance from the outset of the church for times of worship-centred gatherings (Acts 20:7; 1 Cor. 16:2).

[viii] Cf. Acts 18:18; 20:6,16; 21:23.

[ix] Take the following descriptive summary offered in Psalm 146, for example:

Happy are those who are helped by the God of Jacob | Their hope is in [Yahweh] their God. | He made heaven and earth, the sea and everything in it. | He remains loyal forever. | He does what is fair for those who have been wronged. | He gives food to the hungry. | [Yahweh]* sets the prisoners free. | [Yahweh] gives sight to the blind. | [Yahweh] lifts up people who are in trouble. | [Yahweh] loves those who do right. | [Yahweh] protects the foreigners. | He defends the orphans and widows, but he blocks the way of the wicked.

Psalms 146:5-9, NCV

Please note, I have intentional substituted ‘The Lord’ with the personal name of God, as given to Moses at the burning bush. I’ve done this to highlight that ‘the Lord’ is not to be taken as a title, but a personal address. This Psalm is not speaking of any so-called Lord or deity—it cannot be substituted for Zeus, Juno or Baal for example. It refers strictly to the particular God of the Hebrew record.

In contrast to attributes listed in Psalm 146, the theology of Mediterranean antiquity thought there could be nothing like these attributes in a ‘god’; the story of the Jewish scriptures, however, proposes that there is. But, to tie in with the point I am about to make; this Psalm’s description (a creed really) of Jacob’s God (Yahweh) isn’t based on some static deposit of doctrine but rather ongoing events of encounter (Revelation).

[x] If you’re curious about the distinctiveness of Israel’s God in its ancient setting: Rabbi Jonathan Sack’s commentaries within his Covenant and Conversation, especially Genesis and Exodus are extremely valuable. Abraham Joshua Heschel’s highly acclaimed book, The Prophets is also refreshing. I’d also recommend anything by Walter Brueggemann, especially his Old Testament Theology, and John Walton’s excellent Lost World of… series.

[xi] To be sure, the Bible acknowledges humanity’s search for God and our need for meaning. But it’s not the central theme. In the Hebrew story, God declares his passion and love for humanity far more than humanity declares their love for God. God, in the OT, refers to himself as Father and to us as his child, over and over, but seldom, if ever, does anyone refer to God personally in such a way. And as for loyalty; humanity is all over the place, running after so-called gods and man-made gods left, right and centre. But God’s pursuit and loyalty toward us is…, well, as one psalmist described it, ‘it remains forever.’ Scripture is not a reminder of how good we are in seeking God. It’s a powerful reminder of how faithful God is in his pursuit of us.

[xii] Abraham Joshua Heschel, God in Search of Man: A Philosophy of Judaism (Harper Torchbook, Harper & Row, Publishers, New York, 1966), p.136

[xiii] Genesis 3:9

[xiv] God’s question is the second question recorded in the narrative. The first question, by contrast, is delivered by the ‘serpent’ into the ears of humanity, ‘Did God really say…?’. The two questions stand in poignant juxtaposition. God’s question is seeking reconciliation, inviting trust, calling for intimacy. The former question is seeking to sever our trust of God and send us hiding. The wider story then is a matter of which question we incline our ear toward, and Scripture is the record of people responding to the question of God.

[xv] Psalm 23:6

[xvi] Genesis 12:1

[xvii] Referring, of course, to Marcion of Sinope in the second century.

[xviii] To quote Heschel again: ‘Heedfully, we stare through the telescope of ancient rites…’ (Ibid, p. 141)

[xix] Christopher J. H. Wright, The Mission of God: Unlocking the Bible’s Grand Narrative (InterVarsity Press, Nottingham, England, 2008) p. 279

[xx] T. F. Torrance, Incarnation: The Person and Life of Christ, with his Addendum: Eschatology (IVP Academic, Downers Grove, IL, 2008), p. 298

Leave a comment